Ever squinted your eyes and tried to imagine something that’s only in your head?

That’s how it was for those of us who looked over the rail yards and abandoned warehouses of inner northwest Portland some 20 years ago. Rundown and dilapidated, it was a sight that even the best of us squinters had trouble overcoming.

And yet, slowly, a largely forgotten part of Portland’s past became an urban icon of living unlike anything the country had ever seen: A unique blend of verve and vibrancy, with more than a passing nod to Portland’s uncommon brand of originality.

Today, the Pearl District has earned a worldwide reputation for urban renaissance. Diverse, architecturally significant, residential communities thrive here. Galleries rub shoulders with restaurants, shops open to parks, and no one has to squint anymore to see the magic that’s taken hold.

The Pearl is the story of a vision that comes to life. That story has a beginning, and a middle, but to those who have been a part of the transformation – there is no end. Future plans will assure this “pearl” of a place becomes even more: more sustainable, more livable, more inviting, and more groundbreaking.

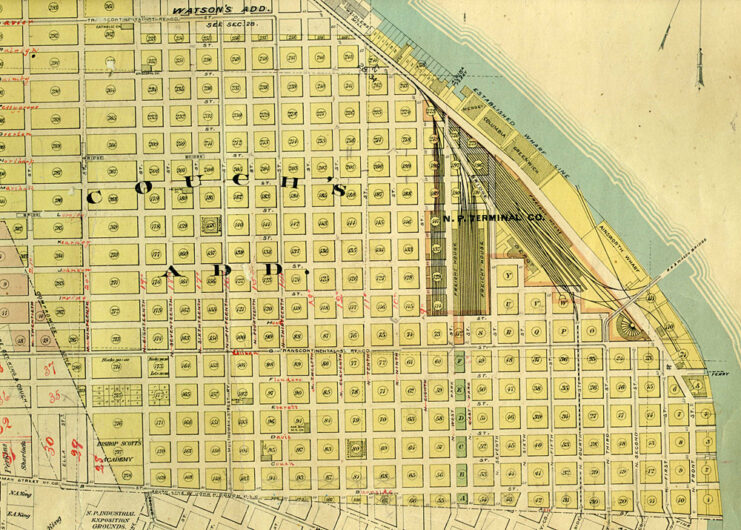

The Pearl District was originally platted as part of Couch’s Addition in 1869 (shown above), and the area around the North Park Blocks was developed primarily with one and two-story houses which were home to mostly blue-collar European immigrants. The North Park Blocks contained the first park block dedicated to exclusive use by women and children, and later the first supervised children’s playground.

In 1896, Union Station was built.

In 1905 the Lewis and Clark Exposition spurred a huge jump in Portland’s population and expansion of the rail yards at the north end of the district. “Empire Builder” James J. Hill, informed Portland’s business elite of the planned arrival of his Portland & Seattle Railway promising the community faster and easier access to cities and markets in the East. This railroad was later named the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (SP&S).

This news began a rather interesting battle of wills between Hill and his rival Edward Harriman, who controlled the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads. Harriman enjoyed dominating the Portland market and had little interest in letting Hill expand in this market.

In a rather clandestine move, Hill purchased the land between N.W. 10th and 12th Avenues and Hoyt Street and Front Avenue through the Security Savings and Trust Company, so as not to signal his intentions to Harriman. Upset by Hill’s grab for prime land near Union Station, the Harriman-controlled Northern Pacific Terminal Company, which owned the Station, refused to allow P&S passenger trains access.

Hill responded by converting one of his rail yard freight houses at the corner of Hoyt St. and 11th Avenue into a passenger depot. Known as North Bank Station, it handled passenger trains to Chicago and the east, Seattle, Astoria, and Southern Oregon until World War I. Intercity passenger trains continued to run until 1931. At NW Hoyt Street, famous luxury trains such as the Empire Builder and the North Coast Limited prepared for their journeys east. A few blocks further, freight that fed the City’s economy dominated the daily activity of the district.

Hill envisioned a seamless service of trains and ocean liners between Portland and San Francisco. He built two luxury ocean liners the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific, which sailed from Flavel at the mouth of the Columbia River near Astoria.

From 1915 until the end of World War I, well-dressed travelers boarded the Steamer Express train at North Bank Station for a scenic ride to Flavel where the ships sailed for San Francisco.

When passenger service stopped, the Hoyt Street Yards continued to handle freight trains and service locomotives until the merger of the SP&S into the Burlington Northern Railroad in 1970. Over the next two decades, the rail yard declined and when the land lease held by the railroads expired, they were abandoned and the remaining brownfields were sold. While the trains are now gone, several brick freight houses remain as luxurious townhomes. Warehouses have been torn down to make way for Jamison Park. The Roundhouse has been replaced by the construction of a 14-story building of luxury condominiums.

Although Hoyt Yards is now a fashionable residential and cultural center, the grittiness of steel, brick and strong-willed visionaries can still be felt in this vibrant and historic neighborhood.

Fifty years ago the area north of Lovejoy was the location for Hoyt Street Rail yards very busy roundhouse and staging area. Today it has been replaced with the luxury Lexis on the Park and Pinnacle condominiums and Tanner Springs Park.

By 1910, the multi-story warehouses and commercial buildings, which characterize the Pearl District today, had become predominant and the area became known as the “Northwest Industrial Triangle”. It was an epicenter of production and activity. One of the oldest of the existing buildings in the neighborhood, the circa 1904 Modern Confectionery Company building was espoused as one of the largest candy manufacturers on the West Coast until the 1930s.

The Central Door Company did business at the northwest corner of 13th & Glisan. As indicated by murals on the building, they sold palte and window glass, mirrors, door moldings and roofing materials from 1906 to 1920, exporting goods to Great Britain, Asia, Africa and South America. In 1921, a musical instrument dealer named Sherman Clay and Co. moved in. They left in 1927 but returned to the Pearl in 2004.

In 1929, the Blumauer-Frank Drug Company built a new warehouse at 14th and Irving – the modern-day Irving Street Lofts. From this giant warehouse, they supplied drug stores across the country with everything from pharmaceuticals to flashlights to soda fountain fixtures.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Portland was a national epicenter of furniture manufacturing and the Pearl, which remains a furniture mecca today, sat at the head of the table. Both the Gadsby Building at 13th and Hoyt and the Wool Grower’s Building at 14th & Johnson participated in the furnishings boom.

Many other former manufacturing and warehouses remain in the Pearl District, mostly now converted to housing and retail uses. The area of 13th from NW Davis north to Johnson Street, with its loading docks and alley-like feel, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The United States Post Office’s main processing facility for all of Oregon and southwestern Washington was built in the Pearl in 1964, next to Union Station. This location was chosen in order for the post office to be able to better serve towns outside the Portland metro area.

At the southern end of the district Henry Weinhard, who had purchased an existing brewery, the City Brewery, in 1864, moved his operations to a then-two block site in the Pearl on West Burnside Street. Business boomed, and between 1865 and 1872 two additional blocks to the north were purchased.

As many breweries also owned the saloons that sold their beer at the time, a large business empire owning properties throughout the Northwest, from San Francisco to Canada was run from here. Weinhard’s Brewing business continued to expand to the point where he even offered to pipe beer directly to the Skidmore Fountain. Civic leaders declined this offer. By 1890, the brewery produced 100,000 barrels of beer annually.

The present buildings were completed in 1908 in order to meet the expanding brewing needs of the Henry Weinhard brewing empire, now serving the Pacific Northwest and even the Philippines and China. Once Prohibition was enacted, the brewery managed to survive by brewing near-beer (a brew of less than 0.5 percent alcohol), syrups and sodas – such as root beer, becoming a local bottler of national brands. Vanilla cream and other syrup products were marketed as “Gourmet Elixirs”.

Mergers with and sales to other breweries occurred over the years. A merger with competitor Portland Brewing brought the Blitz name into the formal name of the brewery. Arnold Blitz, who had owned Portland Brewing, became Chairman of the new Blitz-Weinhard Company. The new company took 20 years to modernize the brewery and recover from Prohibition, which ended in 1933. In 1979, Blitz-Weinhard was sold to the Pabst Brewing Company.

Pabst then sold the brewery to Stroh Brewing Company in 1996. The last and final sale of the company in 1999 had major effects on the brewery building. Stroh’s sold the Henry Weinhard’s brand to Miller Brewing Company, and moved all Henry’s brewing operations to the Olympia Brewery in Tumwater, Washington. After nearly 135 years of continual operations, the Weinhard Brewery brewed its last beer on August 27, 1999. It was put up for sale the following month.

Starting in the 1950s, the area reflected the dynamics affecting central urban areas nationwide. Transportation patterns increasingly shifted from water and rail, to roads and highways and subsequently, interstate freeways and air. The primary users relocated, leaving the District increasingly vacant and marginalized.

These conditions created an area whose low rents attracted a diverse range of new tenants and users. The District became an “incubator” for start-up businesses. It became a convenient location for artists seeking inexpensive space and a casual environment. Warehouse buildings were as dwellings, legally and illegally, introducing a new resident population. The District became an eclectic mixture of auto shops and art galleries. It became the mildly eccentric and quirky home of individuals and businesses that valued its proximity to the downtown, without its formality or expense.

While it’s difficult to conceive now, prior to 1990, abandoned warehouses, long-forgotten industrial sites and blue-collar cafes dominated the Pearl District. Like all pearls of value, the area took time to develop. In 1971, Powell’s Books opened and soon became a Portland landmark. In 1978, Ted Savinar became one of the first artists to move to the Pearl, renting 3,000 square feet for $100 a month.

By the mid-1980′s, the first art galleries had arrived resulting from the number of artists who now inhabited the area, attracted by low-cost lofts. It was the beginning of a major Northwest migration. Even prior to the purchase of the Brewery Blocks and Hoyt Rail Yards, adventurous and savvy investors like John Gray, Al Solheim, John Carroll and Pat Prendergast began to buy up old warehouses in the district and began converting them into unique living spaces. Art galleries and eateries followed close behind.

Much of the redevelopment of the Pearl District was the result of collaboration between the city and private sectors. In the early 1980s, the Pearl District became the focus of planning efforts by the Portland Development Commission. Work that ensued included an urban design study, followed by the 1988 Central City Plan, the 1992 River District Vision Plan and the 1994 River District Development Plan.

Those efforts culminated in the River District Urban Renewal Plan, which was adopted in 1998 and provided tax increment financing for improvements within the district. In 2000, a 26-member steering committee, comprised of city officials, developers, community leaders, planners, designers and others, representing a wide range of viewpoints, met monthly over the course of a year to discuss the future of the Pearl District, to re-evaluate current plans and policies, and to focus on the development priorities for the neighborhood.

In addition to the steering committee, an executive committee met in between the steering committee meetings to provide advice on the planning process and to make initial recommendations to the steering committee. As a result, the ultimate vision for the Pearl was espoused in a 105-page document dubbed the “Pearl District Development Plan, A Future Vision for a Neighborhood in Transition”, and the plan was adopted in October of 2001 by the City Council.

The revitalization of the Pearl District has played a critical role in Portland’s housing strategy and in achieving regional and state goals for growth management. Success in creating a high-density urban neighborhood has helped relieve pressure to expand the UGB and protect rural resource lands.